When comparing asthma rates across income levels in our Community Health dataset:

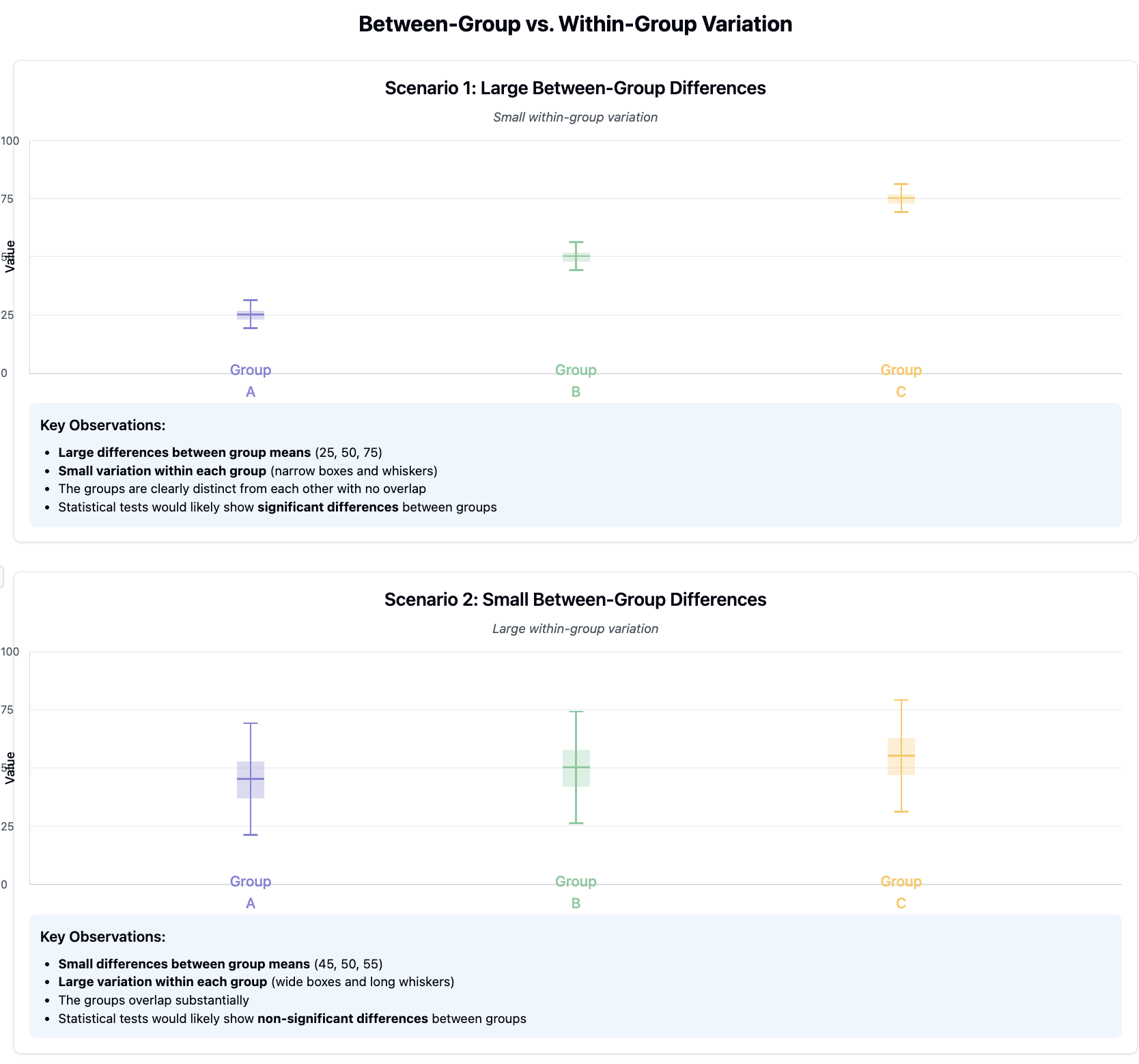

Within-group variation: The range of asthma rates among neighborhoods within the same income category (e.g., high-income neighborhoods might have asthma rates ranging from 5% to 12%).

Between-group variation: The difference in average asthma rates between income categories (e.g., high-income neighborhoods averaging 8% versus low-income neighborhoods averaging 15%).

If within-group variation is small (neighborhoods within the same income category have similar asthma rates) and between-group variation is large (different income categories have noticeably different average asthma rates), we might reasonably conclude that income level is associated with asthma prevalence.